Urban Design and Public Health - Reflections on Fredrick Law Olmsted in the Time of Coronavirus

This month, a temporary emergency field hospital opened in Central Park to provide additional capacity to handle the outbreak of the coronavirus in New York. The 68-bed facility, housed in over a dozen white tents, was erected for overflow patients from the Mount Sinai Hospital in coordination with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). To many, it seems surreal to see the park repurposed for a public-health crisis. For just this reason, it is also a good reminder of the park's historical connections to public health, as well as the intersections of urban planning and public health more broadly.

Fredrick Law Olmsted, with Calvert Vaux, famously created the "Greensward" plan that gave form to Central Park. Olmsted, the so-called father of American landscape architecture, has had a lasting impact on parks and urban parkways across the United States. Part of his legacy was the work continued by his son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., and his nephew, John Charles Olmsted.

Growing up, I knew the name Olmsted, as his work and influence had shaped many of the places I regularly visited in my hometown in Washington State. The Olmsted Brothers conceived a system of parks connecting the burgeoning city of Spokane to nature in the early 20th century. Their work created some of the most celebrated neighborhoods and parks in the city. For me, they gave shape to the boulevards where I rode my bike with friends; allées of trees separating neighborhood streets perfect for playing hide-and-seek; and hills that by happenstance were ideally graded for sledding in the winter. At one point, I lived in a home adjacent to a park developed under the Olmsteds’ vision. I could walk out my front door, under a canopy of Ponderosa pines. At the first junction of the trail, within a hundred steps or so, I could either arrive at a basalt outcrop in a naturalistic setting or enter a pavilion incorporated into a European renaissance-style garden.

My appreciation of these park landscapes expanded during my first semester at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Professor Margaret Crawford presented a history of urban interventions in a discourse on 'the problems and promise of the city'. She presented Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.'s work, including Central Park, as part of a campaign for public health and a response to the mid-19th century overcrowding and health problems in the city. She illustrated the squalid condition of the worst parts of the city with Jacob Riis' striking black and white images of the "Other Half" (If you are not familiar with Riis's work, you can perhaps recall the disorder of the slums and the plight of the urban poor depicted in Martin Scorsese's 2002 movie, Gangs of New York).

In this historical context, Central Park was an urban intervention with manifold ambitions to address several pressing societal challenges. Among them, the eradication of disease and contagions associated with epidemics. New York City had confronted many cholera and yellow fever epidemics in the19th century. At the time, urban parks were promoted as a remedy to eradicate disease and promote health. The environmental connections to health and well-being became a prevailing idea at the time. In fact, Olmsted’s biography further establishes his connections to public health. Though Olmsted is best known as a landscape architect, during the Civil War, he led a commission – essentially a precursor of the Red Cross – focusing on preventing disease and promoting public health.

Learning is enriching, but not necessarily in a strictly additive way - because you acquire new knowledge. Learning is especially expansive when a little new information reframes something you already knew - when a shift in perspective allows you to see something familiar, differently. Crawford's class on the histories and theories of urban intervention had that effect on me; it reframed many places I thought I already knew well. She not only provided an additional way of looking at urban landscapes, but she also revealed a rich history of ideas and practices promoting public health through urban planning.

The landscapes of my hometown were intentionally designed to be places where a community would thrive; they were not only the places where I incidentally played with friends and family. I was merely proof that these urban landscapes continued to have their intended impact, decades after they were founded. The parks’ naturalist features belie the fact that they were designed and engineered; they were the exponent of reforms for urban health and an integral part of the urban infrastructure for developing a healthy society.

Several years later, I would have the opportunity to apply these insights from Professor Crawford’s class to a 770-acre development centered on sustainable development and health. The development was an innovation district for the health sciences, however, the overarching ambitions were to improve community health, broadly, through urban planning. Easier said than done. Though urban nature is usually easy to appreciate, to some it can appear as a luxury rather than a necessity. It may seem axiomatic to claim that, ‘you can’t put a price on health,’ yet, we do it all the time. And, too often, we are unwilling to pay the price required. My review of the local planning documents of the district development I led revealed both a long-standing declaration of the importance of green space, as well as a lack of investment to realize the city’s vision.

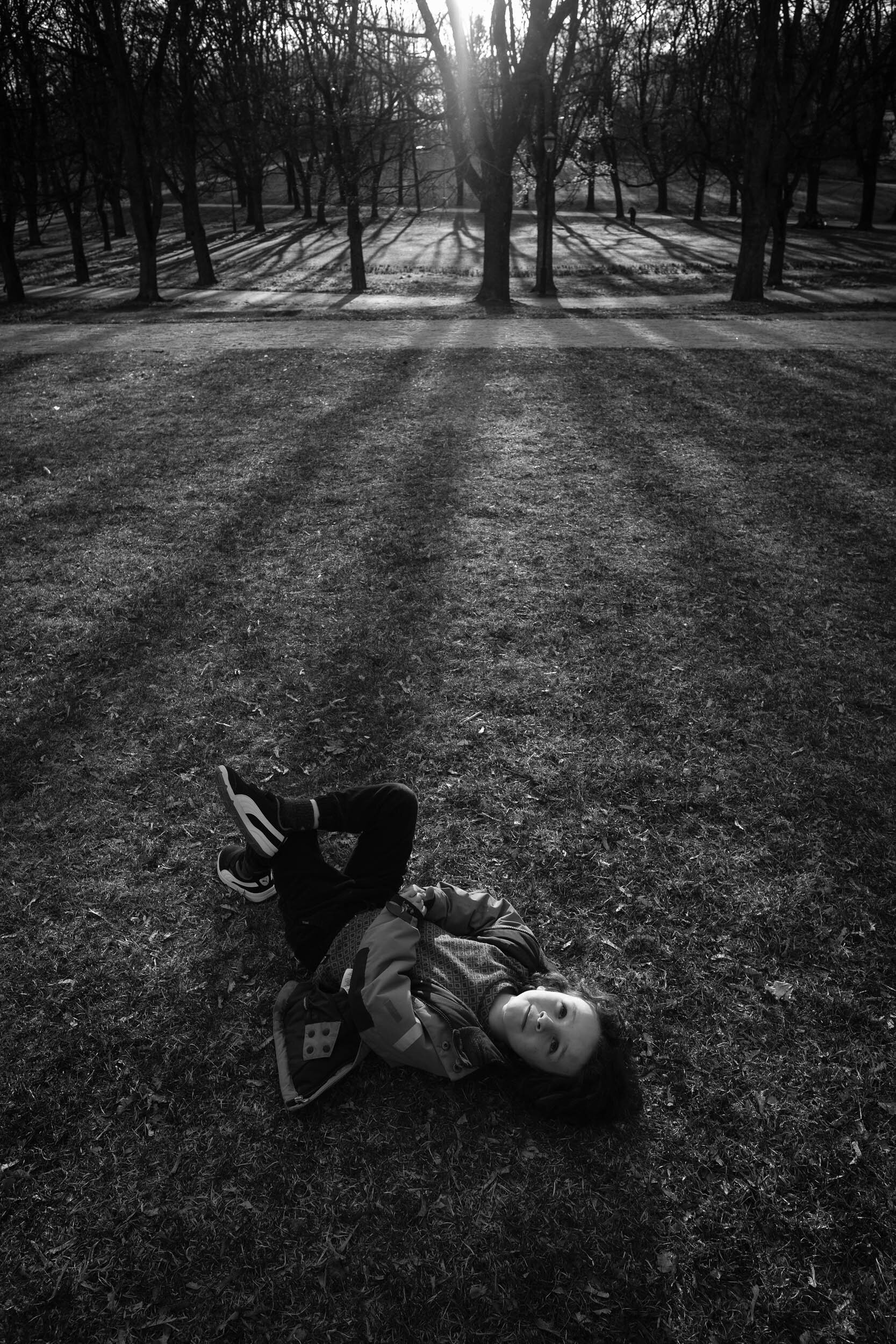

Frognerparken, Oslo Norway

When we get through this pandemic, we will again meet our neighbors in local parks, runners will repopulate the trails, and the medical tents of the field hospital in Central Park will come down. Though there is a desire for things to get back to normal, ideally, we will not go back the way things were. Instead, we will act with a renewed appreciation for the health of our citizens and our cities and an increased commitment to developing communities that support these goals.

It is good to be reminded that the fields of landscape architecture and urban planning were founded with population health as a central concern. Integrating natural areas in urban planning is not only a strategy of placemaking; green spaces are not accessory amenities for recreation. Instead, urban nature should be viewed, prioritized, and funded as a long-standing and effective instrument to improve public health. Our opportunity in the time of the coronavirus is to reframe the way we think about the city and health; to see the familiar spaces of our cities, in a fundamentally different way. We should not need to construct a hospital in a park to see the links between caring for the health of our citizens and the public spaces of our cities.

Sources:

Andrew L. Dannenberg, Howard Frumkin, and Richard J. Jackson, Making Healthy Places: Designing and Building for Health, Well-Being, and Sustainability, By Island Press, 2011

John Duffy. A History of Public Health in New York City 1625-1866, Russel Sage Foundation, New York 1968 (esp. chapter 7, The First Board of Heath, 151-175).

Jane Griffith, “'It's surreal,' nurse practitioner says of field hospital set up in Central Park amid coronavirus pandemic,” NBCNews.com (accessed March 31, 2020).

Madeline Holcombe, Holly Yan and Eric Levenson, “New York's Central Park and harbor are now home to makeshift hospitals”, CNN.com (accessed March 3, 2020).

Witold Rybczynski. A Clearing In The Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the 19th Century. Touchstone, New York, 1999.

Bonj Szczygiel, & Robert Reid Hewitt, “Nineteenth- Century Medical Landscapes: John H. Hohn Rauch, Fredrick Law Olmstead, and the Search for Salubrity,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 74 (4), 708-734.